Static chaos

Scarcity, superstition and survival: how culture reacts in a noisy, furious and stagnant world.

From Pride to protest, June is a month of celebration and tension.

A moment of brightness but also one of unease. We’re saturated with stories yet starved of understanding. Events pass in seconds. Hysteria builds but nothing seems to change. A static chaos.

Adam Curtis argues “we need a language to understand our times.” A map for the emotional and cultural terrain we’re stumbling through.

This edition offers fragments of that language. From artificial scarcity to our fascination with the end of the world. The enemy within to the strange metrics of happiness.

Let’s cut through the noise.

Media

The allure of absence

Why scarcity sells and the hidden costs of wanting what you can't have.

There's a power in something being out of reach. The feeling you get watching a product countdown clock tick to zero or reading "only 1 left in stock." This isn't just about supply and demand, it's a subtle yet potent form of advertising. This approach creates a sense of urgency and perceived value, compelling consumers to act quickly before an opportunity vanishes.

Take Labubu. A jagged-toothed character from Pop Mart’s collectible toy line. Not exactly mass market but it's a phenomenon in certain corners of the internet. The reason? Not quality or price but availability. Drops are rationed. Queues form online and offline. The chase is the thrill.

“A small reminder that even in abundance, we’re governed by what’s withheld.”

It’s a familiar script. Diamonds have long played this game. Though not inherently rare, their supply has been carefully throttled for over a century. The effect? Their value isn't intrinsic but rather derived from the notion that they might run out. De Beers doesn’t sell stones - it sold permanence and the fear that it might slip through your fingers.

What we’re seeing is the rise of artificial scarcity. A strategy where products are deliberately underproduced to make them feel more desirable. It’s used everywhere: from sneaker drops and Hamilton tickets to digital courses and oat milk collabs. Not because supply chains can’t keep up but because brands know that the fewer there are, the more you want one.

Scarcity plays with our psychology. The economist’s old equation - limited supply equals high demand - is now baked into marketing itself. Brands aren’t just making things; they’re making the absence of things. And we're wired to respond. We value what we might lose more than what we already have.

But that emotional rush comes with consequences. Consumers feel pressure to buy fast. Platforms see spikes in impulse purchases. Resale markets bloom, often pricing out the very fans who helped generate the original buzz. The result? A growing mismatch between value and values. Some get what they want. Others get stuck with regret, a lighter wallet or a collection of products they didn’t really need.

There’s an ethical tension at play. Artificial scarcity increases profits and visibility but it can also widen access gaps, feed consumer waste and leave behind a trail of disillusioned customers.

Some websites tell you they don’t track your data but to remember that choice, they still leave a tiny cookie behind. That’s scarcity too: a technical compromise. Not quite true freedom. Not quite full control. Just a small reminder that even in abundance, we’re governed by what’s withheld.

So we’re left with a question: are we falling for the product or for its absence?

Sport

A superstitious playbook

From lucky socks to pre-game rituals, how athletes use the irrational to control the uncontrollable.

Before every match, Serena Williams tied her shoelaces the same way, bounced the ball five times before her first serve and refuses to change her socks during a tournament run. Michael Jordan always wore his old University of North Carolina shorts under his NBA uniform. Footballers step onto the pitch with their right foot first. Cricketers refuse to move from their seat during a partner’s hot streak. These rituals might look irrational but in the high-stakes world of sport, superstition is often as integral as training.

Sport hinges on performance under pressure. For athletes whose careers depend on fine margins and fleeting moments, superstition becomes a way to impose control over chaos. In a world of unpredictable outcomes, rituals provide structure and a psychological anchor.

“In an age of data, metrics and marginal gains, there’s still room for the irrational.”

Superstitions are born from the illusion of influence. When a player scores after wearing a certain armband or eating a particular meal, their brain makes a connection: “this helped.” From there, it becomes habit. And when the stakes are high, breaking the ritual feels like tempting fate.

Psychologists refer to this as “illusory correlation.” The mind’s tendency to link unrelated actions and outcomes. It’s a coping mechanism for uncertainty. Superstition allows athletes to externalise pressure.

But superstition isn’t just a mental crutch. It can have real physiological effects. Repeating familiar rituals calms nerves, sharpens focus and reduces anxiety. The body responds to belief, even if the belief itself defies logic. It becomes part of the performance, not just preparation.

In an age of data, metrics and marginal gains, there’s still room for the irrational. Sport reminds us that even among elite professionals, the mind’s desire for narrative, meaning and ritual endures. Whether it's lucky tape, a handshake routine or an invisible force in the dressing room, superstition remains the hidden sporting playbook.

Storytelling

Apocalypse now and then

We’ve always loved the end.

From ancient flood myths to Hollywood blockbusters, we’ve always told stories about the end of the world. Civilisations may rise and fall but apocalypse endures - an ever-present backdrop to the human imagination. We fear it but we’re also drawn to it. The end times fascinate us not just because of their destructive potential but because they act as a powerful lens into our society. They reveal our deepest values, beliefs and anxieties, offering a unique way to understand what truly matters to us.

In Norse mythology, the world ends in Ragnarok - a great battle, a wolf swallowing the sun and a final reckoning of gods and men. Christianity has Revelation, with fire, plagues, trumpets and judgement. In Hinduism, Kali Yuga marks an age of decline before the cycle begins anew. Even Enlightenment era thinkers, so enamoured with progress, still indulged in visions of collapse, decay and the moral failure of humanity.

“The apocalypse is never abstract - it always echoes the fears of the moment.”

Modern pop culture has only intensified this obsession. Zombie plagues, robot uprisings, climate catastrophe and nuclear fallout. We consume these futures on screen, in novels, in games. Often, these stories reflect the present more than the future. Cold War paranoia birthed radioactive wastelands. The War on Terror brought about dystopias of surveillance and control. Climate fiction now imagines drowned cities and scorched earth. The apocalypse is never abstract - it always echoes the fears of the moment.

But what if the apocalypse really does come slowly, not with fire but with contamination? This is the strange question faced by scientists when they coined the phrase “long-term nuclear waste messaging”. How do you warn people, 10,000 years from now, of a danger so profound they must not disturb a contaminated area?

This is not just a scientific problem but a storytelling one. Enter “ray cats” - a real proposal from the 1980s to breed genetically modified cats that change colour in the presence of radiation, accompanied by songs and folklore warning future generations to beware. This creates a fable embedded in culture.

When the dangers are invisible and the timelines stretch beyond civilisation’s memory, only stories survive. In a way, apocalypse is not just an end - it’s a baton. Something we pass on, not to frighten but to preserve.

Lifestyle

The pursuit of happiness

How the diverse ways countries define contentment illuminate their underlying values.

Every year, the World Happiness Report ranks countries by something almost impossible to measure: happiness. It’s a curious thing, this attempt to quantify joy. To compare the unspoken texture of daily life in Finland and South Korea, in Costa Rica and Croatia.

The report uses data: income levels, social support, life expectancy, freedom to make life choices. These are sensible proxies and the Nordic countries routinely top the list. Finland, Denmark, Norway - they rank highly not just for wealth but for trust, low corruption and access to nature. And yet, if you ask individuals in those countries whether they feel euphoric or even particularly “happy,” many will hesitate.

"We often mistake happiness for something ecstatic.”

This points to something deeper. Happiness, as measured by economists, is often closer to “life satisfaction.” A general sense that things are stable, fair and meaningful. But culturally, we often mistake happiness for something ecstatic. A kind of permanent bliss, constantly visible, endlessly shareable.

That mismatch causes tension. Social media platforms encourage performative joy. Capitalism links happiness with consumption. Self-help industries treat unhappiness as a personal failure. We are told to “live our best lives” even when the world around us feels fractured.

In contrast, the countries that top the report often emphasise something else: modesty. Balance. Community. A sense that enough is, in fact, enough. It’s not a coincidence that the happiest countries also tend to have the smallest wealth gaps or the most accessible healthcare.

Perhaps the pursuit of happiness is less about chasing a feeling and more about cultivating conditions where contentment can grow. Space to breathe. Time to connect. A belief that tomorrow will not be worse than today.

In that light, the report isn’t just a scorecard. It’s an invitation. To rethink what it means to be well and what we might build to make more of us feel that way.

History

The enemy within

The enduring power of domestic paranoia in national identity.

Every empire needs an enemy. But the most dangerous ones are rarely at the gates. They’re inside. Whispering. Plotting. Corrupting the soul of the nation. Or so the story goes.

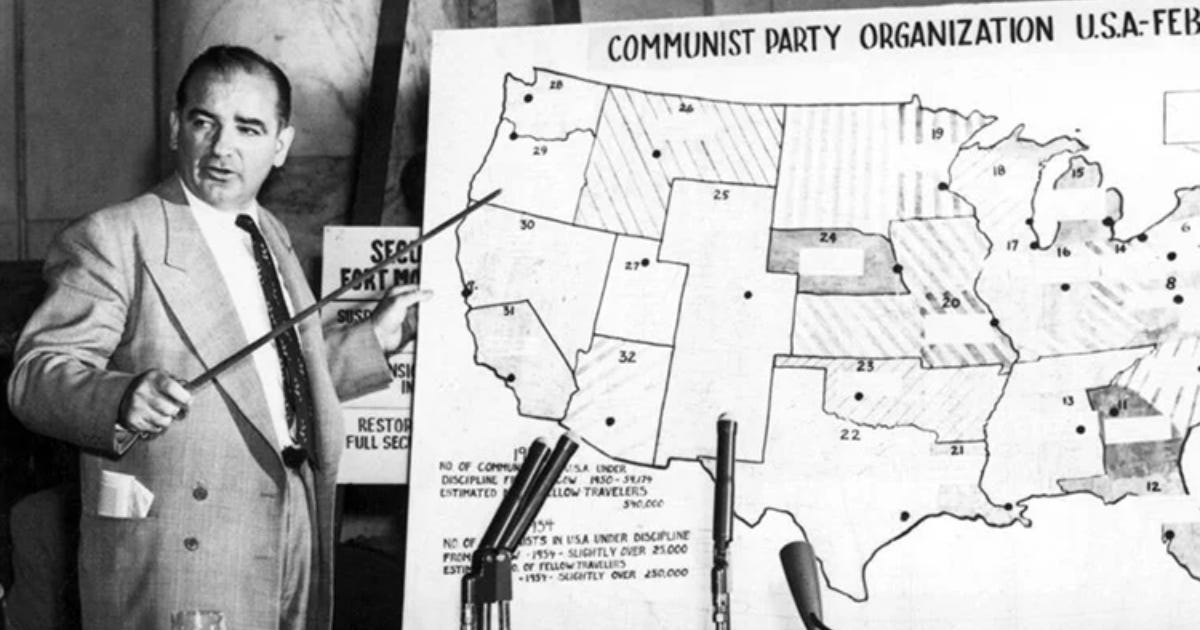

The United States has a long history of this kind of psycho-drama. From the Red Scare to the culture wars, there's a recurring paranoia that the real threat isn't external, it's domestic. Think about the fear of communists in Hollywood, subversives in the classroom or "un-Americans" in government. This isn't just political rhetoric. It's a fear that reshapes politics and warps national identity itself. Patriotism can quickly turn into suspicion and unity can become a form of policing.

McCarthyism was only the beginning. Today's conspiracy-laced discourse, from QAnon to election denial, is built on this same foundational myth. The idea that somewhere, someone within is actively plotting the country's demise. A society consumed by this mindset risks eating itself alive.

“It’s easier to blame the dissident than to confront decline. Easier to seek purity than to accept pluralism.”

Russia tells a similar tale, but with older shadows. The spectre of the traitor is woven into its imperial DNA. During Peter the Great’s modernisation campaign in the early 18th century, he turned westward with ambition and brutality. He built cities, fleets and bureaucracies. But he also saw enemies everywhere. Even his own son, Alexei, was not spared. He was tortured and executed for allegedly conspiring against the state. Reform and repression walked hand in hand. Paranoia became policy.

This "enemy within" mindset is more than politics. It’s psychological. A narrative of rot from within. A nation eating itself while pretending to cleanse. It explains why both America and Russia - despite their ideological differences - often fall into the same traps: moral panics, internal purges and national myths wrapped in fear.

It’s easier to blame the dissident than to confront decline. Easier to seek purity than to accept pluralism. The real threat isn’t always the other - it’s the mirror. And when nations stare too long, they risk mistaking their own reflection for the face of the enemy.

Rhymes

A bold, brassy anthem rooted in wartime resilience, Aaron Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man has echoed through arenas, ceremonies and soundtracks since its 1942 debut. But which iconic war film featured this stirring composition?

Drop your guess below. No googling.

Did something here resonate, spark a thought or remind you of a story? We’d love to hear from you in the comments.

If you enjoyed what you read, please spread the word by subscribing, engaging and sharing it with your network.

Stay curious. Culture awaits.

Until next time,

George